|

For our monthly blog post, we will discuss an exciting upcoming piece of legislation: HB 5429, coming to a Michigan legislator near you! Let’s dive in and see how this house bill will benefit Michigan citizens and us here at CASA. House Bill (HB) 5429 is sponsored by Representatives Christine Morse, Carrie Rheingans, Phil Skaggs, Felicia Brabec, Jasper Martus, Tyrone Carter, Brenda Carter, Julie Brixie, Jenn Hill, Rachel Hood, Julie Rogers, Sharon MacDonell, Carol Glanville, Regina Weiss, Jim Haadsma, Betsy Coffia, Jimmie Wilson Jr., and Jaime Churches. Let’s work through each section of the bill to understand better what is being advocated for! Section 1 of HB 5429 allows the House Bill to be called The CASA Act. From here on, we will refer to the House Bill as the CASA Act. Section 2 defines some CASA terms! For example, a CASA Volunteer is defined as “an individual appointed by a court.” “CASA Child” means “a child under the jurisdiction of the court.” Quite a few terms are outlined and defined in this second section. For the full list of terms, click the first link below to see the current CASA Act! Section 3 begins the part of the CASA Act that outlines that a court may create a CASA Program and the things a CASA Program must do. A key thing to note when we discuss what a CASA Program has to do, these guidelines are in line with Michigan CASA and National CASA standards for local programs. A CASA Program must screen, train, and supervise CASA Volunteers and provide them with the opportunity for 12 hours of training per calendar year. A fun line in this section is that CASA Volunteers be allowed to observe court proceedings after their initial training to become a CASA Volunteer. In Section 7, the CASA Act outlines when a CASA Volunteer is to be appointed to a court case. “Court may appoint a CASA when, in their opinion, a child affected by the proceedings requires the CASA Service, and it is in the child’s best interest.” We have talked in previous blog posts about what Best Interest means. In the CASA Program, Best Interest is defined as “best interest, which means the child is receiving support for their development that allows them to thrive and supports them into a healthy adulthood. Legally best interest factors are central to CASA’s advocacy for children.” For more information on Best Interest, follow the link to our other blog post listed below! Another important part of a CASA Volunteer’s case journey is how they end their involvement in a case. The CASA Act states CASA stop being involved in the case in the following circumstances: -Court Jurisdiction ends on the case -The CASA Volunteer is discharged by the court -With the approval of the Court, at the request of the Program Director Section 9 has the description of what a CASA Volunteer must do within the parameters of their role. These are listed as follows: -Talk to all appropriate parties on the case -Review reports and documents as appropriate -Make recommendations based on the Best Interest Principle, specifically on the child’s placement, visitation with caregivers, and appropriate services -Make sure the case is progressing timely -Prepare and Submit a written report to the court -Monitor the case to ensure the child’s essential needs are met -Make efforts to attend all hearings, meetings, and other appropriate proceedings -May be called as a witness in court proceedings That’s a lot of responsibilities! CASA Volunteers hold a unique position in the Child Welfare System. They have access to a lot of confidential information and use that information to advocate for the child. Here at CASA for Kids, we pride ourselves on having 4 Advocate Supervisors and 2 Training Supervisors that our CASA Volunteers are welcome to contact when they have questions or want support. Good news! The CASA Act has passed through the Michigan House of Representatives and has been sent over to the Michigan Senate for approval. If you are interested in any of the specific language used or want to see how this bill is progressing, check out the links below! See the bill at the below link! https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/billintroduced/House/pdf/2024-HIB-5429.pdf Updates on progress can be found here: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(qdf0mqrebtfqa0rfrdbhnfup))/mileg.aspx?page=GetObject&objectname=2024-HB-5429 https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/billanalysis/House/pdf/2023-HLA-5429-25A0A2AA.pdf Best Interest Blog Post https://www.casaforkidsinc.org/news/archives/02-2024 This May our blog is about the child welfare system through the years in the United States! In honor of our gala theme of Children and Families Through the Ages, let’s walk through the history of the US and how we have supported families and children.

One of the first things to note is that, even as a colony, the US has had some kind of support for children. Before the American Revolution, the first permanent orphanage was established in Savannah, Georgia by Reverand George Whitefield. By the early 1900s impoverished children were taken into institutional care, given apprenticeships, or worked in factories. In 1906, legislation was introduced to create a federal children’s bureau. In 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt held a White House Conference in support of the Mother’s Pension Movement. This movement became one of the first times the idea that “children should not be removed from their homes of origin due solely to poverty”. While this conference is a great start, the pensions that came from this movement were not available to women of color, mothers with children born out of wedlock, or divorced mothers. In 1912, the Department of Labor and the Federal Children’s Bureau were both established. The Federal Children’s Bureau dealt with investigating matters related to child and maternal well-being. This was the first major federal law in the United States focusing on infant and maternal health, and it provided money for health services. For the first time, charity organizations were no longer the main sources of welfare, and the federal government provided financial relief for families in need. The Children’s Bureau lobbied and campaigned for the passage of the Keating-Owen Act of 1916. This act prohibited the interstate commerce of goods manufactured by children. This is the first attempt to curtail child labor! Despite this act being supported by President Wilson, it would be ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1920. Let’s move on to the 1920s! The last Orphan Train leaves New York City in 1929. These trains of orphaned children would take children from the city to the countryside to families who could provide them with stable environments. These children were orphans or had living mothers who could not afford to raise them. As we move to the 1930s we start to see attempts to codify the fledgling child welfare system! You will start to see the framework for our modern system. The Social Security Act of 1935. Amendments in 1939 added benefit payments to the spouse and minor children of a retired worker and survivors’ benefits to dependents of an eligible retiree who had died. In 1935, the National Youth Administration was established. This program aimed to train out-of-school youth between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five as well as provide funding for high school, undergraduate, and graduate students. In 1934 with the Indiana Reorganization Act and the Johnson-O’Malley Act, we see the federal government wade into tribal autonomy and the practice of funding Native American schools. Firstly, these acts established the principle of tribal self-determination which means the federally recognized tribes were given the ability to determine for themselves how their governments would run. Another component of these acts was the provision of federal funds to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This new funding was given for K-12 and vocational education in federal and locally administered public schools, as well as loans for Native American youth to attend college. In the 1940s we do not see as much legislation in regards to child welfare as we do in other decades. This author would argue this is due to a global conflict taking a lot of the US’s attention and resources. However, we do see more support provided for military families during this time. The federal government established the Emergency Maternity and Infant Care Program (EMIC) to provide free pregnancy and postpartum health care to the wives of military personnel in lower pay grades and to their young children. EMIC served approximately 1.2 million mothers, supporting the births of about 1 in 7 Americans born between 1943 and 1946. In the 1950s we see consolidation and organization of the child welfare system. In 1953 President Eisenhower established the cabinet-level Department of Health, Education, and Welfare which encompasses the majority of federal programs affecting child well-being. President Eisenhower also establishes the President’s Council on Youth Fitness. This program is aimed at encouraging youth to lead active lifestyles. If you have ever run a timed mile in gym class this is where those standards come from! We would be remiss not to mention the biggest change for children in the U.S. In 1954 the decision was made in the court case Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka. This decision made it so no public school could practice segregation of black children from white children. In a future blog post, we will discuss the effects this had on Michigan as a state. The 1960s were a time of great upheaval and societal change. There are few better examples than the changes to the child welfare system! In 1961 federal funds for foster care were provided for the first time. The 1961 Social Security Amendments established the “Flemming Rule,” creating a foster care component to Aid to Dependent Children (ADC). This gave states more money to support foster placements and children who have been removed from their homes of origin. In 1962 Henry Kempe coined the term “Battered Child Syndrome”, further drawing national attention to child abuse. Battered Child Syndrome is usually defined as the collection of injuries sustained by a child as a result of repeated mistreatment. By 1966, every state had passed legislation requiring better reporting and intervention in cases of child abuse. In 1962, President Kennedy successfully worked with the US Congress to create a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Subsequently, they set up training grants for teachers of deaf and “handicapped” children. These grants were approved in 1961 and 1963 and signed into law by President Kennedy. This decade saw legislative strides being made in terms of childhood nutrition! In 1966 the Child Nutrition Act made the Department of Agriculture send funds to states so they could serve breakfast for low-income students. A few years later in 1969, the Summer Food Service Program was established. This program helps to distribute food over the summer school break for children until they are eighteen years old. We see the change in the approach to social safety nets around mental health as well! The 1963 Comprehensive Community Mental Health Centers Act authorized federal funding to build public and nonprofit clinics for child and adult mental health. In 1965, Medicaid and Medicare were established! In that same year, we see the establishment of Head Start! This program serves children at or below the poverty line and gives them access to preschool that may otherwise be unattainable. The 1970s saw the passage of significant and rather famous legislation regarding to the child welfare system and supporting America’s families. The Supplemental Food Programs for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) was signed into law in 1971. It was created to provide food vouchers, commodities, and nutrition programs to pregnant mothers, postpartum mothers, and families who had children up to the age of five in their household. For those with experience in the child welfare system, this next law is perhaps the most significant and famous. In 1974, the Child Abuse and Treatment Act (CAPTA) came into effect. CAPTA gave federal funds to states to improve their responses to allegations of child abuse and neglect. It was key in connecting child welfare workers to early intervention services and developing plans with service providers to better support families and children. Following CAPTA came the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in 1978. This law is one the most significant legislative efforts to honor a child’s community of origin. The goal of this act was to give tribal authorities and leadership a seat at the table in child welfare cases when it concerned a tribal family. In effect it helped keep children in touch with their tribal communities and extended family members. Speaking of significant legislative efforts on behalf of families, in 1975 the Child Support Enforcement (Title IV-D) Program was created. This program helped to establish paternity cases and help to secure child support payments when ordered by the court system of non-custodial parents. Next, we will move on to the 1980s! In 1980, the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act was passed. Its purpose was to establish a program of adoption assistance; and strengthen the program of foster care assistance for needy and dependent children. As well as improve the following programs: child welfare, social services, and aid to families with dependent children. Later attention would turn to teenagers aging out of the child welfare system. In 1986, the US Congress authorized the Independent Living Program. This program was geared towards teenagers and adolescents who were on the verge of aging out and did not have the skills necessary for independent living. It continues to support those aging out of the child welfare system! In the 1990s there was quite a bit of legislation put in place to address areas previous legislation had not addressed. In 1993, out of concern that states were focusing too little attention on efforts to prevent foster care placement and reunify children with their families, Congress established the Family Preservation and Family Support Services Program. Several years later, in 1996, TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) is introduced. This program varies state by state but overall the program provides time-limited assistance to families. Several years later in 1997, The Adoption and Safe Families Act, created the timeline for the termination of parental rights at 15 out of 22 months post removal of the child or children. This act also requires a permanency hearing every 12 months to speed up the process of finalizing child welfare cases. The Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 replaced the Independent Living Program with the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP). In addition to increasing funding, CFCIP expanded the existing independent living program to include services for both adolescents making the transition from foster care to self-sufficiency and former foster youth up to age 21. We will be lumping a few decades into one section! We will see the focus of child welfare legislation move to be more focused on keeping children in their home of origin. We see in 2000, The Strengthening Abuse and Neglect Courts Act of 2000. This act aimed to reduce the backlog of abuse and neglect cases that plagued child welfare courtrooms. It also passed the ability to automate case tracking and data collection. Imagine keeping all of that information not on a computer! In 2018 we see the passage of the Family First Preservation Act. This act provided funding for states and tribal authorities to expand available prevention services to keep children in their homes of origin. In our program, this saw us expand to provide more advocacy services for children who remain in their home of origin for the duration of their child welfare case! Learning our history is key for us here at CASA for Kids. We know that we must learn from our past, especially regarding systemic issues within the child welfare system. Our team is committed to learning and growing from our collective experiences, helpful and harmful; so we can best advocate for children and strengthen families in future decades. https://blogs.millersville.edu/musings/a-history-of-child-welfare-in-the-united-states/ https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/child-welfarechild-labor/child-welfare-overview/ https://www.masslegalservices.org/system/files/library/Brief%20Legislative%20History%20of%20Child%20Welfare%20System.pdf https://firstfocus.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Childrens-Policy-History.pdf March 31st is Transgender Day of Visibility. This day was created by Michigan’s own Rachel Crandall Crocker in 2009. She is the founder and executive director of Transgender Michigan. An organization that focuses on educating the people of Michigan on gender identity and expression as well as injustices that transgender individual and their families face, as well as providing advocacy and support for transgender individuals and those who are perceived as gender variant. In 2021, President Biden federally proclaimed and recognized the day, and it has now been utilized to honor transgender Americans and their contributions. The Transgender Day of Visibility is different from the Transgender Day of Remembrance. The day of remembrance is to honor and remember every person who has been murdered for being themselves. The Day of Visibility is utilized to honor Transgender individuals who have made history and advocated for Transgender rights.

There is an overrepresentation of LGBTQ+ youth in the child welfare system. According to Youth.gov, “Studies have found that about 30 percent of youth in foster care identify as LGBTQ+ and 5 percent as transgender, in comparison to 11 percent and 1 percent of youth not in foster care.” LBGTQ+ youth may experience different stressors and removal reasons than their peers. A Human Rights Campaign defined these extra stressors as “Many LGBTQ+ youth have the added layer of trauma that comes with being rejected or mistreated because of their sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression.” According to the Trevor Project, “28% of LGBTQ youth reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives — and those who did have two to four times the odds of reporting depression, anxiety, self-harm, considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to those with stable housing.” What do we do? How can we improve the outcomes for these youth? One way is to ensure that youth going through the child welfare system have a supportive adult who stays with them for the duration of their case. CASA and our advocates support children regardless of their gender or sexual identity. One of the youths we serve spoke with us about his experience with his CASA. He said, “Everyone deserves one. It’s a whole vibe. They tell important people your side, and you don’t feel alone.” Through CASA’s advocacy, the courtroom uses his preferred pronouns and the name he chose for himself. He is now in a placement that supports and accepts him for himself after several nonsupportive homes and significant mental health concerns. Today, he can thrive, focus on his future, such as what he wants to be when he grows up, and engage in hobbies like drawing. At CASA, we know firsthand how critical safety, stability, support, and permanency are to developing minds and strong families. Transgender youth and adults are people, just like any of our CASA children, who deserve a chance to thrive! If you are interested in learning more about this issue and what other advocacy groups are doing. Follow the links below! https://www.transgendermichigan.org/ https://youth.gov/youth-topics/lgbtq-youth/child-welfare https://www.thehrcfoundation.org/professional-resources/lgbtq-youth-in-the-foster-care-system https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs https://www.saluscenter.org Throughout the year, we will periodically post about terminology and system-specific terms CASA uses. This month, in honor of our new training group, we will do a deep dive into terms we commonly use. You will hear CASA talk about how we advocate for children's best interests. What does best interest mean and who determines it? The best interest of the child or children has some surprising origins within the child welfare system. We will talk about three of these philosophies of best interest.

Firstly, we have the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article Three specifically talks about the Best Interests of the Child. “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” Secondly, we have the International Federation of Social Workers. They state “The best interest would be support through infancy to adulthood. This includes access to health, education and community support, critical in developing the child’s perception of society and his/her responsibilities to the wider community.” Lastly, we have the Michigan law 722.23 Section 3 of the Child Custody Act of 1970. It is written (this has been condensed down to not weigh anyone down with legal jargon) “As used in this act, ‘best interests of the child’ means the sum total of the following factors to be considered, evaluated, and determined by the court:

Now that we have looked at three separate entities and how they define best interest of the child, we can see they overlap in certain aspects. Overall they all state that best interest means the child is receiving support to their development that allows them to thrive and supports them into a healthy adulthood. Legally best interest factors are at the center of CASA’s advocacy for children. However, we know each child and their family is unique and their best interest must be assessed with that unique lens. Every recommendation CASA volunteers make in the court system and community on behalf of a child is centered on what is in the child’s best interest, taking into consideration their unique needs, values, and cultural identity. To learn more about these factors consider going to the following links: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(s1st0jfjx24myh4vn2pv5oo4))/mileg.aspx?page=GetObject&objectname=mcl-722-23 https://www.ifsw.org/the-best-interest-of-the-child/ https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child January is National Slavery and Human Trafficking Month. January was first designated in 2010 to increase awareness of human trafficking. Here at CASA, we provide advocates for various cases, including those involving aspects of human trafficking. With a lot of media attention and people speaking about human trafficking, we believe it is worth it to dispel some myths as well as give a bigger picture of what human trafficking looks like. What is Human Trafficking? The Department of Homeland Security defines Human Trafficking as “the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act.” Who are the survivors of human trafficking? When we talk about human trafficking, people often think of the movement of women or girls for non-consensual commercial sex. Having this view on human trafficking is understandable, as popular media focuses on the stories of female and young survivors. However, according to the Polaris Project, 35% of total survivors of human trafficking were not female. A majority of non-female survivors were being trafficked for labor purposes. Much like child abuse and neglect cases, there is not a single set of risk factors that could lead one to being trafficked. Survivors come from all walks of life in the United States and other countries. What does it look like? Often media portrays human traffickers as strangers who force people into these situations. According to the Polaris Project, in 2021, approximately 91% of human trafficking survivors had a close or previous relationship with their trafficker. Similar to grooming practices with sexual abuse cases, human traffickers do not start out with trafficking immediately. Usually, it is a slow increase in behaviors and pushing their limits until the survivor is involved in trafficking. Regarding trafficking across countries' borders, citizenship or gainful employment can be promised. Another way people are coerced is through access to addictive substances. If you take one thing away from our blog, let it be this: there is no set victimology. There is no one set way that people become trafficked. Survivors come from every walk of life; think about those in our farm fields, those who engage in commercial sex acts, and those who build our large commercial properties. Please support systems in place that assist people out of these situations. Check out these national resources for more information on human trafficking! https://polarisproject.org/myths-facts-and-statistics/ https://www.rainn.org/ https://humantraffickinghotline.org/en https://www.state.gov/humantrafficking-about-human-trafficking Helping Survivors https://helpingsurvivors.org/ Recently the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has proposed a rule to strengthen the implementation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Before we get into what the proposed change is, we need to know what the legislation currently covers.

When the Rehabilitation Act was signed into law in 1973, it created a national law that protects qualified individuals from discrimination based on their disability. This section of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is where we get the Section 504 plans for students in schools. This requires recipients of federal funding to provide students with disabilities with appropriate educational services. The proposed change to the rule would update, clarify, and strengthen the regulation for Section 504. One change that is proposed would ensure medical treatment decisions are not based on any biases, stereotypes, judgments, or beliefs that people with a disability have less value. Another proposed change, that directly impacts CASA’s work with children, is that there will be requirements to ensure nondiscrimination in the areas of parent-child visitation, reunification services, child removals and placements, guardianship, parenting skills program, foster and adoptive assessments, and in and out of home services. This proposed change is in direct response to the variety of discriminatory barriers parents, caregivers, and foster parents have encountered when attempting to access child welfare programs. It is wonderful to see changes happening to benefit children wit disabilities and their support systems. With these proposed changes, CASA will continue to advocate for children to have access to services that are appropriate for their unique needs. Want to learn more about this change? Click here! Recently, the US Department of Health and Human Services announced a proposed rule that will direct child welfare agencies around the country to “fully implement existing protections for LGBTQ+ youth in foster care.” The Human Rights Campaign, HRC, praised the move, stating, “This proposed rulemaking is an important step toward ensuring LGBTQ+ youth in foster care, who make up nearly one in three of the children in the foster care system, have the safe, healthy, and affirming environments they need in order to thrive.” The proposed rule would require child welfare agencies to give youth access to evidence-based behavioral and mental health care that supports their sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. As well as banning the use of “conversion therapy.”

Here at CASA, we support every effort that helps support children as they navigate growing up and the foster care system. Our volunteers undergo initial training on how to advocate for children of diverse backgrounds and ongoing training on supporting children of diverse backgrounds. Several studies conducted since 2019 have reported that 1 in 3 children in foster care identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community. It is critical to support all children in foster care, especially youth in the LGBTQ+ community, as they are over-represented in foster care. While there is a long way to go in supporting youth who belong to the LGBTQ+ community, this is an excellent start to advocate for healthier outcomes for these youth. As a part of ensuring LGBTQ+ youth have access to affirming environments where they can thrive, CASA’s recruiting and training team is developing resource lists for our communities. Here are some resources for LGTBQ+ youth in Barry, Eaton, and Ingham counties!

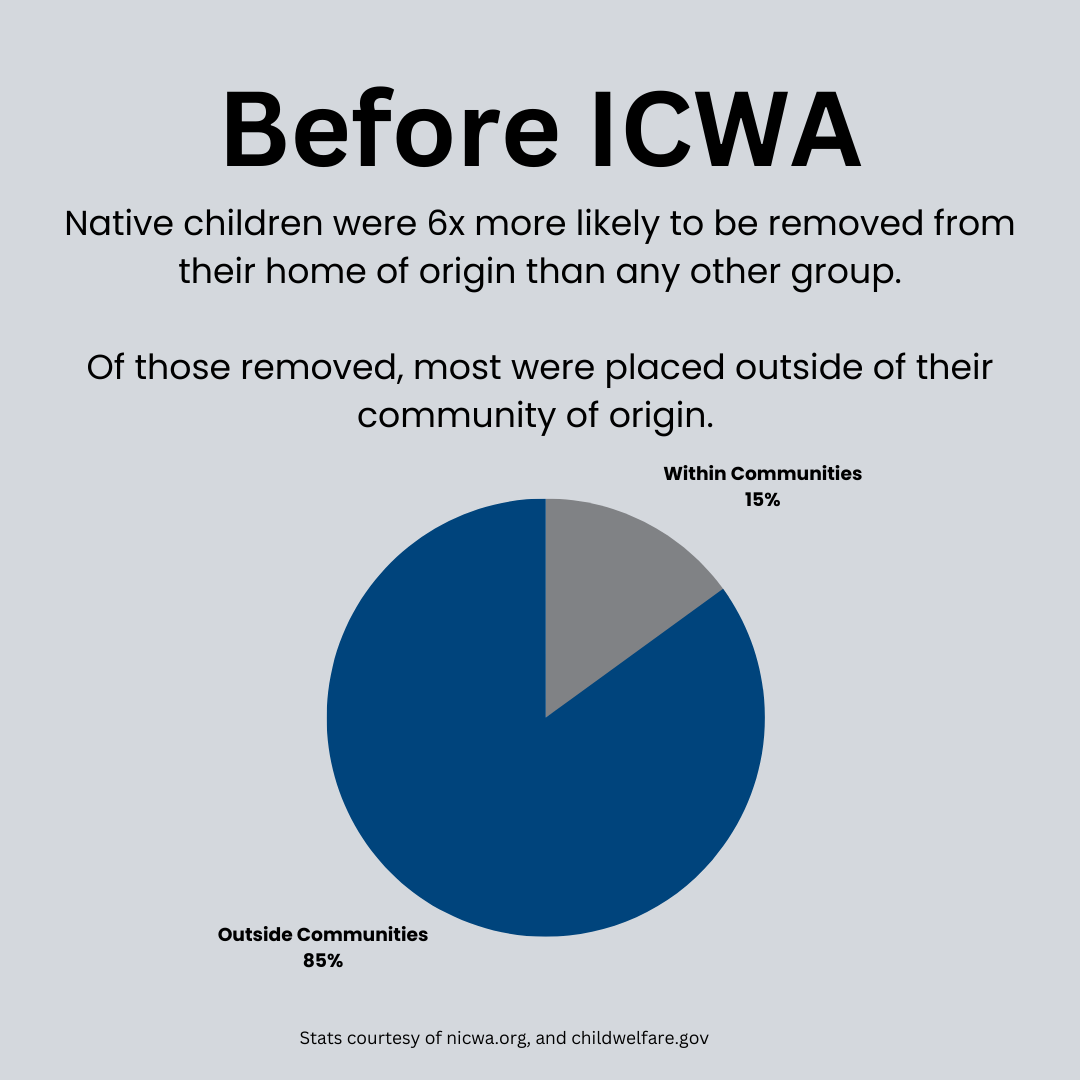

To learn more and review our sources click on the link below: https://www.hrc.org/press-releases/human-rights-campaign-hails-proposed-federal-rule-that-would-help-protect-lgbtq-children-in-foster-care On June 15th, 2023 the United States Supreme Court upheld ICWA as constitutional. You may also see this decision labelled as Haaland v. Brakeen. The majority opinion wrote that the law was constitutional and protected the rights of Native children. But what is ICWA? How did it come about? And what does this ruling mean for child welfare going forward? ICWA or the Indian Child Welfare Act is a law designed to protect Indigenous children so they have the ability to observe any cultural traditions they have. It was first signed into law in 1978 by the United States congress. This law was put in place to protect and enshrine the ability of Native children to be attached and integrated in their communities or origin. ICWA states that when an Indigenous child is removed from their home their placement has to be with family, then with members of the same tribe if their is no extended family members, then with members of another tribe if there are no tribal members available to take the child. This is to continue a child’s ability to be integrated in their own culture and community. Another aspect of ICWA is to provide “active efforts” to Native families. This means providing services within in a certain time frame, including the tribe on decisions involving the family, and including parents in decisions when it comes to their child’s cultural practices, as well as other casework aspects. Secondly, ICWA is designed specifically to combat the effects of Boarding Schools, Industrial Schools, and placements that do not allow children to honor their culture. Historically, Indigenous children were removed and placed outside their community more often than other children. In Michigan ICWA was codified in state law through was 2012 Public Act 565, which created the Michigan Indian Family Preservation Act (MIFPA) in 2013. In addition to ensure ICWA standards in Michigan, MIFPA goes beyond the ICWA standards to ensure that there are protections for indigenous children and families in both the juvenile and family court systems. What does this mean going forward? The rights of Indigenous children will continue to be abided by and honored. Supreme Court Justice Gorsuch has a quote that best underscores what this means for the future of families -  Author: Keeley Robinson

P.S. There is a great article from the Native American Rights Fund that goes into a deeper dive on the history that lead to ICWA coming into being that can be read here, along with other sources. NCWWI NARF MI COURTS |

AuthorOur blog is written in conjunction between members of our Outreach Team and our Executive Team! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed